Hello fiber lovers! We have all wondered what is the warmest yarn to spin and knit. If you ask the internet what is the warmest natural fiber the consensus says Qiviut. While researching this, I couldn’t find a site that explains how this was tested so I decided to test it myself. I went into this expecting to see Qiviut was the warmest fiber and I just wanted to see by how much was it the warmest. My testing results were shocking!

I also made a video covering this topic. If you prefer the video format you can see it here.

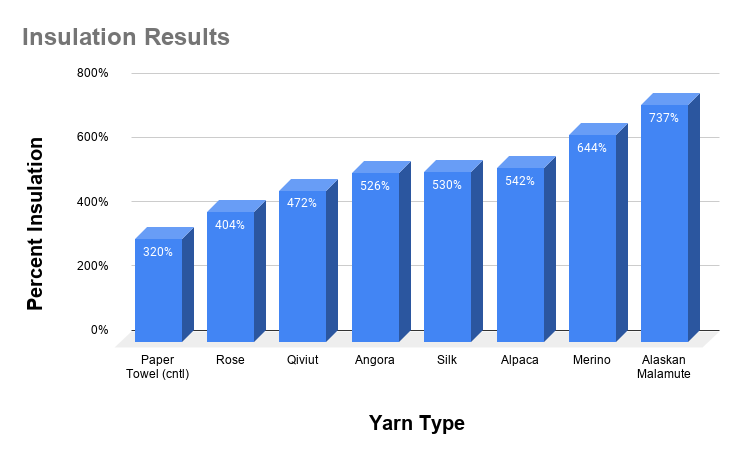

Results

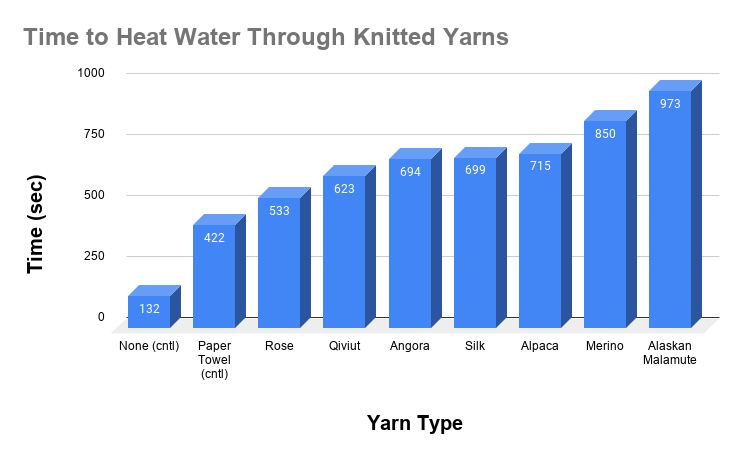

I’m not one to build suspense so the results are directly below. These results show how well different knitted test swatches insulate compared to no insulation. The testing methods section at the end of this post goes into the full details of how the testing was done.

These are not the results I was expecting. I collected results multiple times just to make sure the results were consistent and they were. All the test swatches are as close to the same density and thickness as I could get. I did some measurements on the thickness and they are all between 4 and 4.7mm. Even if I adjust for the slight difference in thickness it doesn’t make a difference in the rankings here.

From my testing this is how I’d rank these different yarns from warmest to coolest.

- Alaskan Malamute

- Merino

- Alpaca

- Silk

- Angora

- Qiviut

- Rose

Paper Towel (Control)

This was included to give a control to compare against. Obviously a single sheet of paper towel isn’t a great insulator, but it is significantly better than not having any insulator. It took 3.2 times as long to heat through a paper towel than it took to heat the water with no insulator between the hot plate and the water.

Alaskan Malamute

The Alaskan Malamute is a dog that was bred to haul heavy freight as a sled dog. So it should be no surprise that the their hair when turned into yarn is extremely warm. It was my warmest sample I tested by a significant margin. The yarn only uses the dog’s soft undercoat so in addition to being very warm it is extremely soft. The sample was probably the softest of any of the samples I had and it had a beautiful halo.

The problem with this sample is this isn’t a common type of fiber which makes it hard to get and really expensive. The good news is the next warmest fiber on my list is much easier to get so let’s look at that one.

Merino

This is the type of wool people say to use when you want a warm sweater, and it didn’t disappoint. It suprised me that it was the second warmest yarn in my tests. I expected some of the other exotic yarns to do much better, but after rerunning the tests several times I’m convinced in my testing with my samples it is the second warmest yarn. An added bonus is this is a fairly easy to get yarn and less expensive than most of the other yarns on this list.

Alpaca

Alpaca’s performed well in this test. It turns out it isn’t quite as warm as Marino, but it did get third place in my testing. Alpaca’s are native to cold environments in the Andes Mountains and their fiber is an excellent insulator. I did some looking online to see how arm Alpaca is and it was certainly classified as a warm fiber. like that my testing shows how it compares to others.

Silk

I wasn’t sure how silk would perform with insulating since it is from a silk worm that uses the silk to form a cocoon to protect themselves during metamorphosis, where as wool is there to keep sheep warm. That said, silk did a good job in my tests. It took around 5 times as long for heat to permeate the silk test swatch as compared to having no isolator. Silk is also a light weight and soft fiber.

Angora

Angora fiber is the undercoat of Angora rabbits. When I searched for the warmest natural fibers it was usually Angora and Qiviut at the top of the list. So it was a shock that this fiber came in fifth place. To be fair the fibers that placed third through fifth were all very close so you could argue that Angora was basically tied for third. Still based on what I read online I was expecting this to do better than Merino wool, but it is well behind that. On the plus side this fiber was extremely soft and had a great halo.

Qiviut

The internet says this fiber from a musk-ox is warmest fiber. Many places say it is eight times warmer than wool. This is where my testing completely disagrees with those statements. I found Qiviut was not even close to as warm as Merino wool or a bunch of other fibers. The sample I purchase, which is the most expensive yarn I’ve ever purchased by the ounce, was from what seems like a reputable Qiviut fiber dealer and it was very soft.

I’m still a bit in shock that that Qiviut tested so poorly in my testing. I have verified my test swatch is similar in thickness to my other samples. I would like to test another sample of Qiviut someday, but I just can’t justify that expense for this blog post right now. That said even if I find a sample that is much warmer, it would still be difficult to beat some of the other fibers tested here.

Rose

This knitted test swatch was the worst insulator of the knitted test swatches I tested. There are certainly times where you want a beautiful knitted garment, but you don’t want it to be too warm. Maybe it’s a warm summer night, but you want to wear that shawl on the beach. In those cases Rose yarn would be a good option.

This is fiber made from rose plants and turned into yarn. It is a cellulose fiber so I didn’t expect it to be a good insulating fiber. While I didn’t test it, bamboo would probably have similar properties and is more commonly found in yarn.

Update – There is some controversy about whether rose fiber is from rose bushes. Check out this article for another point of view.

Does Human Body Warm Impact These Results?

Testing how warm people perceive different fibers is a completely different test. I’m including this section because it’s going to be a common question and I want to try and address it.

The human body is constantly generating heat at some point the insulating properties of the clothing you are wearing keeps enough of the heat on your body comfortably warm. So while the percentages above can help you see the relative insulating properties of different fibers, you shouldn’t take these numbers to be how warm they keep you in all cases. The human body is constantly adapting and switching from warming to cooling states so there is fairly wide range of temperatures you can be comfortable. Because of that even though some fibers might be better insulators, you might not even notice a difference in many situations.

From talking with many spinners and knitters, I believe softness of a fiber likely impacts how warm people think a fiber is. The mind is powerful, and just as sugar pill placebos can help reduce certain ailments I’m pretty sure people’s perception of what a warm fiber is will help keep you a little warmer. This isn’t going to keep you warm in really harsh conditions, but if you are comparing two different sweaters on a cool fall evening perception your mindset could well make a difference. I don’t have any papers directly addressing this this type of behavior so feel free to treat this point with some skepticism if you require that kind of proof.

Some fibers keep you warmer when wet. This page does a good job of explaining why wool has this property. In certain conditions this effect will affect how warm clothing feels.

Thickness is going to matter. If you have two scarves made from the same type of yarn, but one is knitted so the scarf is thicker then it will feel warmer. Use this to your advantage by trying to knit thinner garments when you want them cooler and thicker garments when you want them warmer.

So taking all this into account if you really wanted to figure out what knitting clothing feels the warmest, a scientific way to do that would be to create simliar thinkness/gage mitten out of several different yarns. Then have a lot of people try it on and put their hand in a cold box. You shouldn’t let them see the mitten or know which one it is. Ideally you would even put some extra covering over their hand so they couldn’t feel the fiber so that perception had minimal impact on this test. Then ask them to rate the warmth of the different mittens on a scale of 1 to 10. While I’d be interested in this kind of test it was beyond the scope of this post.

Testing Methods

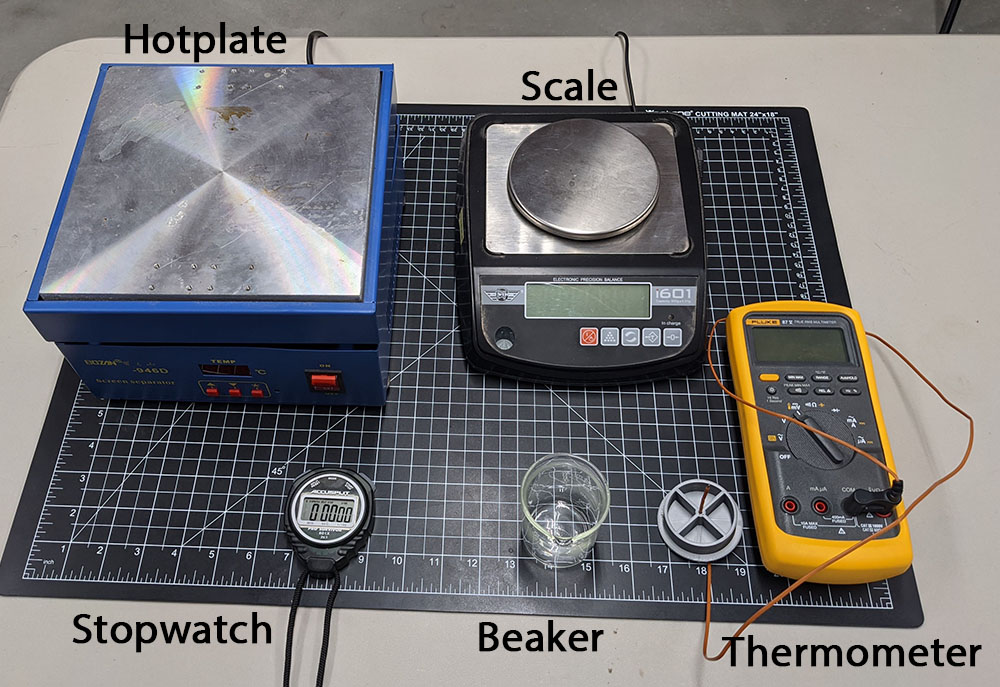

I want to explain how I am testing this for a few reasons. The first is I couldn’t find anyone explaining this and as I mentioned in the introduction it’s important. Another reason I’m explaining my testing method is because it isn’t a standard method. The best way to do this testing would be to use thermal conductivity meter, but these chambers seem to cost over $10K USD which is way beyond my budget. I am using a modified version of the guarded hot plate method which is one of the most commonly used methods for measuring the thermal conductivity of insulation materials. Chapter 2.1 in this document explains this method. My version is modified because I only cared about a the relative difference in the insulation properties and thus didn’t need the much more complex Poensgen apparatus described in this paper.

Here are the tools I use in my method:

- Thermometer (I’m using a Fluke DMM with a temperature probe)

- Scale (I use this to measure 50 grams of water)

- Stopwatch

- Hotplate (I’m using a solder reflow plate because it’s accurate and has a controllable temperature)

The basic procedure is I put 50 grams of room temperature water into a small beaker. Then I put the insulator (a knitted test swatch) on the hot plate set to 120 degrees Celsius. Then I put the beaker of water on the insulator and measure the time it takes to raise the water by 10 degrees Celsius while using a 3d printed cover for the beaker to hold the thermometer in a consistent position. The longer it takes to heat the water the better the knitted test swatch insulates the beaker from the hot plate.

The main issue with this test is I don’t have it calibrated to give an output of thermal conductivity in the standard units of watts per meter-kelvin. It would be nice to have that, but a system that does that is more complex and beyond the scope of this project. Instead my measurements are only useful to compare them again each other. My testing methods work because I want to find the warmest yarn and my test will tell me which of the yarns I’ve tested is the warmest relative to the other yarns.

I want to give a huge thanks to Kathryn, who goes by the the alias CraftMeHappy on Ravelry for donating many of these test swatches.